Social Stories and Autism

Ranking:

Social stories are a type of prompt or script used to help autistic individuals understand and behave appropriately in certain situations.

Social stories and other social scripts are based on the idea that some autistic people have difficulty understanding and/or behaving appropriately in certain situations, such as meeting other people for the first time.

Social stories provide descriptions of a particular situation, event or activity, which include specific information about what to expect in that situation and, sometimes, what to do in that situation.

Some social stories are written on single sheets of paper, others are written in booklets and some are recorded onto tape or video. The author of the story may read it to the individual with autism, record it so that it can be played back as required, or the individual may read it for himself.

Our Opinion

There is a small amount of high quality research evidence (four randomised controlled trials) on the use of social stories as an intervention for autistic children or adults but the results are mixed.

There is a considerable amount of low quality evidence (more than 80 single case design studies) to suggest that social stories may reduce unwanted behaviours and increase social interaction in some autistic children.

Determining if social stories provide any significant benefits for autistic individuals is not currently possible. We must wait until further research of sufficiently high quality has been completed.

If you are going to use social stories, we recommend that you should follow the 10 defining criteria established by Carol Gray. This should ensure that each story is written to meet the specific needs of the individual child in a specific situation.

Disclaimer

Please read our Disclaimer on Autism Interventions

Aims and Claims

Aims

The aim of social stories is to increase someone’s understanding of specific social situations, to make them more comfortable in those situations, and possibly to suggest appropriate responses when in those situations. According to Attwood (2000),

“A social story is written with the intention of providing information and tuition on what people in a given situation are doing, thinking or feeling, the sequence of events, the identification of significant social cues and their meaning, and the script of what to do or say; in other words, the what, when, who and why aspects of social situations”.

Claims

There have been various claims made for social stories as an intervention for autistic people. For example, Gray (1993) claims that “Social stories serve a wide variety of purposes. They appear to be particularly helpful in facilitating inclusion of students with autism in general education classes. They have been used successfully to introduce changes and new routines at home and at school, to explain the reason for others’ behaviors, or teach new academic and social skills".

Audience

Social stories were first developed for use with primary school autistic children but have since been adapted for use with a wide range of people, including autistic adolescents and adults and people with other conditions, such as language impairment, learning disability etc.

According to Gray (1993), “Social stories are most likely to benefit students functioning intellectually in the trainable mentally impaired range or higher who possess basic language skills. Social stories have been used successfully with both elementary [primary] and secondary students”.

Key Features

Social stories are a type of prompt or script used to help autistic individuals to understand and behave appropriately in certain situations.

Social stories provide descriptions of a particular situation, event or activity, which include specific information about what to expect in that situation and, sometimes, what to do in that situation.

Social stories are different from other prompts or scripts in that they are meant to follow a set of 10 defining characteristics. For example, authors of social stories are supposed to follow a defined process to share accurate information using a content, format, and voice that is descriptive, meaningful, and physically, socially, and emotionally safe for the audience.

Developing the story

According to Sansoti et al (2005) there are several steps needed to develop a social story:

- Identify the social situation that the child finds difficult (for example, waiting for someone else to finish playing with a toy).

- Identify the key features of the situation (for example, where a situation occurs, who is involved, how long it lasts, how it begins and ends, what occurs).

- Identify why the child is likely to behave inappropriately in this situation

- Identify the child’s strengths and weaknesses, as well as their perspective on the situation they find difficult.

- Share all of this information with the child and other relevant individuals, such as the child’s teacher, to check that you have understood the situation correctly.

- Write the social story, ensuring you take account of the child’s ability to understand it.

Language/ Type of sentence

Social stories are written from the child’s perspective, using positive language in the first person (“I”), and in the present tense.

A social story may consist of several different types of sentence, each of which is designed to do different things.

- descriptive sentences: describe the situation or activity, for example, “I love playing with the big, yellow truck”.

- directive sentences: tell the child what they should do in this situation, for example, “When Jonathan is playing with the truck, I can say, ‘Can I have a turn please?’”.

- perspective sentences: describe how other people will feel in this situation, for example, “Jonathan likes to play with the yellow truck, too”

- affirmative sentences: express a shared value or opinion, for example, “It is OK to wait”.

- control sentences: identify strategies that the child can use to remind himself how to behave, for example, “I can play with the truck when Jonathan has finished his turn”.

- cooperative sentences: explain who will provide help and how, for example “ “My teacher will help me stay calm while I wait for my turn”.

Carol Gray suggested that there should be at least double the amount of “describe” sentences as “direct” sentences.

- Describe sentences = descriptive + perspective + co-operative + affirmative.

- Direct sentences = directive + control.

Format of stories

The length of the story and the medium in which it is presented should be personalised to the needs of the child for whom the story has been written.

Social Stories can be read, either independently or by a caregiver, or they can be presented through audio equipment, a computer-based program or via videotape.

Using the story

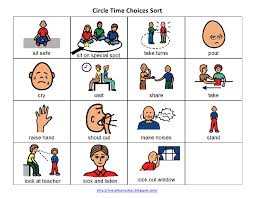

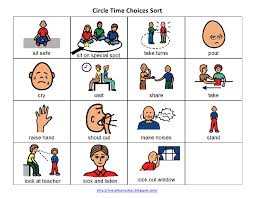

Social stories are normally introduced one at a time allowing the child time to focus on one concept or skill. Stories can be implemented once a day or just prior to the situation described. For example, if a child is currently working on a story about sharing toys, you can review the story right before play time to remind the child what might happen and how they should respond.

Example of a social story

The following social story is reproduced from the City of Toronto, Early Childhood Services Team tip sheet on creating social stories (date unknown). The type of sentence of indicated in brackets.

“My name is Matthew.

I love playing with the big, yellow truck (descriptive).

Jonathan likes to play with the yellow truck, too (perspective).

Jonathan pushes the truck on the floor and puts blocks in it (descriptive).

He likes to make “beep-beep” noises when he pushes the truck (perspective).

When Jonathan is playing with the truck, I can say, “Can I have a turn please?” (directive).

I wait until he has finished his turn (directive).

It is OK to wait (affirmative).

My teacher will help me stay calm while I wait for my turn (co-operative).

My teacher is happy when I wait for my turn (perspective).

When Jonathan is finished, it is my turn (descriptive).

I have fun playing with the truck (descriptive)”

Cost and Time

Cost

In theory, social stories can be provided at no cost since they can be written by anyone who understands the basic principles.

In practice, you may need to pay for any equipment and materials you use (such as audio equipment). Alternatively, you can buy some social stories from commercial suppliers or download them for free from some websites.

If you undertake any training, you may have to pay for things like learning materials, travel and accommodation.

Time

The amount of time it takes to create an individual social story will depend on how much time you spend on each of the steps needed to develop the story. The amount of time it takes to actually read the story will depend on a number of things including the length of the story, the format it is presented in and the ability of the recipient to understand it. For example, you may have to read some stories to some people on a daily or weekly basis.

Risks and Safety

Hazards

There are no known hazards for social stories.

Contraindications

There are no known contraindications (something which makes a particular treatment or procedure potentially inadvisable) for social stories.

Suppliers and Availability

Suppliers

theory, anyone can write social stories, including parents, teachers and health care professionals. In practice, it is possible to buy materials or to attend training courses on how to write the stories from a variety of suppliers in the UK, US and other countries.

Credentials

There are no formal, validated registered qualifications for people using social stories, since any individual, parent or carer can write them. However, Carol Gray recommends that you should follow 10 defining criteria when using them. According to the CarolGraySocialStories.com website, accessed on 7 March 2017,

“These criteria guide Story research, development, and implementation to ensure an overall patient and supportive quality, and a format, “voice”, content, and learning experience that is descriptive, meaningful, and physically, socially, and emotionally safe for the child, adolescent, or adult with autism.”

The current version of these criteria (“Social Stories 10.2”) is set out in the Additional Information section of this factsheet.

Related Suppliers and Availability

History

Carol Gray, former consultant to autistic students in Jenison Public Schools in Michigan, USA, wrote the first social stories in 1990 and has been developing her ideas and practice ever since.

According to the CarolGraySocialStories.com website, accessed on 7 March 2017, “The Social Story philosophy was in place long before the first social story; the definition of Social Stories and information on how to write them has seen more of an evolution. There are sound basics that have been there since 1990. The changes that have occurred have been in response to experience with Social Stories, research findings, and protection of the quality, integrity, and safety of the approach.”

Gray first published the defining characteristics (criteria) in Social Stories 10.0 (2004). Subsequent revisions and reorganisation resulted in Social Stories 10.1 (2010) and Social Stories 10.2 (2014). The current version of these criteria (“Social Stories 10.2”) is set out in the Additional Information section of this factsheet.

“These criteria guide Story research, development, and implementation to ensure an overall patient and supportive quality, and a format, “voice”, content, and learning experience that is descriptive, meaningful, and physically, socially, and emotionally safe for the child, adolescent, or adult with autism.”

The current version of these criteria (“Social Stories 10.2”) is set out in the Additional Information section of this factsheet.

Current Research

We have identified more than 80 studies of social stories as an intervention for autistic individuals published in English language, peer-reviewed journals. These studies included more than 250 participants aged from three years old to adult but the majority of studies looked at children.

Some of the social stories were written by/provided by academic researchers, some by teachers and some by parents. Some were presented as plain text, some were presented with pictures, some were presented electronically and some were presented as songs. Some were presented in multi-media formats.

The studies were conducted in a variety of locations including schools, clinics and family homes. Some studies were conducted in several different locations.

Most of the studies looked at social stories as standalone interventions, while a small number of the studies looked at social stories combined with other interventions (such as video modelling) or compared social stories with other interventions (such as visual schedules).

- Many of the studies reported decreases in inappropriate behaviour (such as speaking too loudly or being aggressive) in some participants.

- Many of the studies reported increases in desired behaviours (such as complying with instructions or interacting with peers) in some participants.

- Some of the studies reported limited or mixed results. For example, Malmberg et al, 2015 reported that social stories were less effective than video modelling and Leaf et al, 2012 reported that social stories were less effective than the teaching in interaction procedure.

Status Research

Status of Current Research Studies

There are a number of limitations to all of the research studies published to date. For example

- The overwhelming majority of studies consisted of single-case designs with 3 or less participants.

- Some of these single-case design studies used extremely weak methodologies (such as simple AB reversal designs) or were descriptive case studies only.

- Some of the studies did not provide enough details about the participants, such as whether they had a formal diagnosis of autism, intellectual ability etc.

- It is not clear how many of the studies actually followed the defining characteristics of social stories described by Gray.

- Very few of the studies examined the different elements of social stories (such as sentence type, format of presentation etc.) to determine which, if any, are the most important for which groups of people.

- Very few of the studies compared social stories with other interventions which are designed to achieve similar results, such as video modelling.

- Very few of the studies examined if social stories can be used as one of the elements within comprehensive, multi-component, treatment models

- Most of the studies did not state if the social stories provided any beneficial effects which lasted in the medium to long term.

- Most of the studies did not state if the social stories provided any practical benefits in real world settings.

- Most of the studies did not involve autistic people in the design, development and evaluation of the research.

For a comprehensive list of potential flaws in research studies, please see ‘Why some autism research studies are flawed’

Future Research

Summary of Existing Research

There is a small amount of high quality research evidence (four randomised controlled trials) on the use of social stories as an intervention for autistic children or adults but the results are mixed.

There is a considerable amount of low quality evidence (more than 80 studies) to suggest that social stories may reduce unwanted behaviours and increase social interaction in some autistic children.

There have been a number of scientific reviews of social stories as an intervention for autistic individuals. The majority of these have concluded that there is insufficient evidence to determine if social stories are effective for autistic people. For example,

- Bozkurt and Vuran (2014) concluded ‘… social stories should not yet be considered as evidence based practice for teaching social skills to individuals with ASD”.

- McGill et al (2015) stated “… the current meta-analysis indicates that the effectiveness of Social Story interventions is limited and that they should be used cautiously as a therapy for treating problem behaviours in children and adolescents with ASD”.

- Qui et al (2015), stated “Social stories have been shown to be effective in decreasing inappropriate behavior. However, mixed results were found when social stories were used to increase social communication skills as well as other appropriate behaviors.”

- Reynhout and Carter (2006) stated “Examination of data suggests the effects of Social Stories are highly variable. Interpretations of extant studies are frequently confounded by inadequate participant description and the use of Social Stories in combination with other interventions. It is unclear whether particular components of Social Stories are central to their efficacy. Data on maintenance and generalization are also limited”.

- Rust and Smith (2006) stated “Whilst the existing literature suggests positive findings with respect to the effectiveness of Social Stories, there is considerable variability in the quality of research methodology, with no single study employing comprehensive, stringent standards”.

- Sansoti et al (2005) “Overall, the empirical foundation regarding the effectiveness of Social Stories is limited. Although the published research demonstrates positive effects of Social Stories and provides preliminary support that Social Stories are effective with individuals with ASD, the results of previous research should be considered with caution. Due to a lack of experimental control, weak treatment effects, or confounding treatment variables in the reviewed studies, it is difficult to determine if Social Stories alone were responsible for durable changes in important social behaviors. Thus, it may be premature, based on the current literature, to suggest that Social Stories are an evidence-based approach when working with individuals with ASD”.

Recommendations for Future Research

Future studies should

- Use more scientifically robust, experimental methodologies with larger numbers of participants.

- Provide more details about the participants, such as whether they had a formal diagnosis of autism, intellectual ability etc.

- Ensure that the social stories follow the criteria established by Carol Gray including adequate assessment before a story is created and adequate assessment after the story has been used.

- Examine which elements of social stories (such as sentence type, format of presentation etc.) if any, are the most important for which outcomes for which groups of people.

- Compare social stories with other interventions which are designed to achieve similar results, such as video modelling.

- Determine if social stories can be used as one of the elements within comprehensive, multi-component, treatment models.

- Identify if social stories can be used in areas not previously examined, for example, improving study skills.

- Identify if the social stories have any beneficial effects in the medium to long term.

- Identify if social stories have any beneficial effects in real world settings

- Involve autistic people in the design, development and evaluation of those studies.

Studies and Trials

This section provides details of scientific studies into the effectiveness of this intervention for autistic people which have been published in English-language, peer-reviewed journals.

If you know of any other publications we should list on this page please email info@informationautism.org

Please note that we are unable to supply publications unless we are listed as the publisher. However, if you are a UK resident you may be able to obtain them from your local public library, your college library or direct from the publisher.

Related Studies and Trials

-

Acar C., Tekin-Iftar E., Yikmis A. (2017)

Effects of mother-delivered social stories and video modeling in teaching social skills to children with autism spectrum disorders.

Journal of Special Education.

50(4),

Read Abstract

(New Window)

-

Alzyoudi M.

et al.

(2016)

The effectiveness of using a social story intervention to improve social interaction skills of students with autism.

Journal of the American Academy of Special Education Professionals.

Read Abstract

(New Window)

-

Beh-Pajooh A.

et al.

(2011)

The effect of social stories on reduction of challenging behaviours in autistic children.

Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences.

15

Read Abstract

(New Window)

-

Brownell M. (2002)

Musically adapted social stories to modify behaviors in students with autism: four case studies.

Journal of Music Therapy.

39(2),

Read Abstract

(New Window)

-

Chan J. M.

et al.

(2011)

Evaluation of a social stories intervention implemented by pre-service teachers for students with autism in general education settings.

Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders.

5(2),

Read Abstract

(New Window)

-

Crozier S., Tincani M. J. (2005)

Using a modified social story to decrease disruptive behavior of a child with autism.

Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities.

20(3),

Read Abstract

(New Window)

-

Delano M. E., Snell M. E. (2006)

The effects of social stories on the social engagement of children with autism.

Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions.

8(1),

Read Abstract

(New Window)

-

Graetz J. E., Mastropieri M. A., Scruggs T. E. (2009)

Decreasing inappropriate behaviors for adolescents with autism spectrum disorders using modified social stories.

Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities.

44(1),

Read Abstract

(New Window)

-

Hagiwara T., Myles B. S. (1999)

A multimedia social story intervention: teaching skills to children with autism.

Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities.

14(2),

Read Abstract

(New Window)

-

Halle S.

et al.

(2016)

Teaching social skills to students with autism: A video modeling social stories approach.

Behavior and Social Issues.

25

Read Abstract

(New Window)

Read Full

(New Window)

-

Hutchins T. L., Prelock P. A. (2006)

Using social stories and comic strip conversations to promote socially valid outcomes for children with autism.

Seminars in Speech and Language.

27(1),

Read Abstract

(New Window)

-

Hutchins T. L., Prelock P. A. (2013)

Parents' perceptions of their children's social behavior: The social validity of social stories and comic strip conversations.

Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions.

15(3),

Read Abstract

(New Window)

-

Hutchins T. L., Prelock P. A. (2013)

The social validity of social stories for supporting the behavioural and communicative functioning of children with autism spectrum disorder.

International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology.

15(4),

Read Abstract

(New Window)

-

Hutchins T. L., Prelock P. A. (2008)

Supporting theory of mind development: Considerations and recommendations for professionals providing services to individuals with autism spectrum disorder.

Topics in Language Disorders.

28(4),

Read Abstract

(New Window)

-

Ivey M. L., Heflin L. J., Alberto P. A. (2004)

The use of social stories to promote independent behaviors in novel events for children with PDD-NOS.

Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities.

19(3),

Read Abstract

(New Window)

-

Kassardjian A.

et al.

(2014)

Comparing the teaching interaction procedure to social stories: a replication study.

Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders.

Read Abstract

(New Window)

-

Klett L. S., Turan Y. (2012)

Generalized effects of social stories with task analysis for teaching menstrual care to three young girls with autism.

Sexuality and Disability.

30(3),

Read Abstract

(New Window)

-

Leaf J. B.

et al.

(2012)

Comparing the teaching interaction procedure to social stories for people with autism.

Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis.

45(2),

Read Abstract

(New Window)

-

Litras S., Moore D. W., Anderson A. (2010)

Using video self-modelled social stories to teach social skills to a young child with autism.

Autism Research and Treatment.

Read Abstract

(New Window)

Read Full

(New Window)

-

Lorimer P. A.

et al.

(2002)

The use of social stories as a preventative behavioral intervention in a home setting with a child with autism.

Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions.

4(1),

Read Abstract

(New Window)

-

Malmberg D. B., Charlop M., Gershfeld S. J. (2015)

A two experiment treatment comparison study: Teaching social skills to children with autism spectrum disorder.

Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities.

27(3),

Read Abstract

(New Window)

-

Mancil G. R., Haydon T. F., Whitby P. S. (2009)

Differentiated effects of paper and computer-assisted social storiesTM on inappropriate behavior in children with autism.

Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities.

24(4),

Read Abstract

(New Window)

-

O’Handley R. D., Radley K. C., Whipple H. M. (2015)

The relative effects of social stories and video modeling toward increasing eye contact of adolescents with autism spectrum disorder.

Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders.

11

Read Abstract

(New Window)

-

Ozdemir S. (2008)

The effectiveness of social stories on decreasing disruptive behaviors of children with autism: Three case studies.

Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders.

38(9),

Read Abstract

(New Window)

-

Pop C.

et al.

(2013)

Social robots vs. computer display: Does the way social stories are delivered make a difference for their effectiveness on ASD children?

Journal of Educational Computing Research.

49(3),

Read Abstract

(New Window)

-

Quilty K. M. (2007)

Teaching paraprofessionals how to write and implement social stories for student with autism spectrum disorder.

Remedial and Special Education.

28(3),

-

Quirmbach L.

et al.

(2009)

Social stories: Mechanisms of effectiveness in increasing game play skills in children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder using a pretest posttest repeated measures randomized control group design.

Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders.

Read Abstract

(New Window)

-

Samuels R., Stansfield J. (2012)

The effectiveness of social stories to develop social interactions with adults with characteristics of autism spectrum disorder.

British Journal of Learning Disabilities.

40(4),

Read Abstract

(New Window)

-

Scattone D.

et al.

(2002)

Decreasing disruptive behaviors of children with autism using social stories.

Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders.

32(6),

Read Abstract

(New Window)

-

Scattone D. (2008)

Enhancing the conversation skills of a boy with Asperger's disorder through social stories and video modeling.

Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders.

38(2),

Read Abstract

(New Window)

-

Schneider N., Goldstein H. (2010)

Using social stories and visual schedules to improve socially appropriate behaviors in children with autism.

Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions.

12(3),

Read Abstract

(New Window)

-

Schneider N., Goldstein H. (2009)

Social storiesTM improve the on-task behavior of children with language impairment.

Journal of Early Intervention.

31(2),

Read Abstract

(New Window)

-

Schwartzberg E. T., Silverman M. J. (2013)

Effects of music-based social stories on comprehension and generalization of social skills in children with autism spectrum disorders: A randomized effectiveness study.

Arts in Psychotherapy.

40(3),

-

Tarnai B. (2011)

Establishing the relative importance of applying Gray's sentence ratio as a component in a 10-step social stories intervention model for students with ASD.

International Journal of Special Education.

26(3),

Read Abstract

(New Window)

Read Full

(New Window)

-

Thiemann K. S., Goldstein H. (2001)

Social stories, written text cues, and video feedback: effects on social communication of children with autism.

Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis.

34(4),

Read Abstract

(New Window)

Read Full

(New Window)

-

Thompson R. M., Johnston S. S. (2013)

Use of social stories to improve self-regulation in children with autism spectrum disorders.

Physical and Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics.

33(3),

Read Abstract

(New Window)

-

Wright B.

et al.

(2016)

Social stories to alleviate challenging behaviour and social difficulties exhibited by children with autism spectrum disorder in mainstream schools: design of a manualised training toolkit and feasibility study for a cluster randomised controlled trial.

Health Technology Assessment.

20(6),

Read Abstract

(New Window)

Read Full

(New Window)

Other Reading

This section provides details of other publications on this topic.

You can find more publications on this topic in our publications database.

If you know of any other publications we should list on this page please email info@informationautism.org

Please note that we are unable to supply publications unless we are listed as the publisher. However, if you are a UK resident you may be able to obtain them from your local public library, your college library or direct from the publisher.

Related Other Reading

-

Ali S., Frederickson N. (2006)

Investigating the evidence base of social stories.

Educational Psychology in Practice.

22(4),

Read Abstract

(New Window)

-

Attwood T. (2000)

Strategies for improving the social integration of children with Asperger syndrome.

Autism.

4(1),

Read Abstract

(New Window)

-

Bozkurt S. S., Vuran S. (2014)

An analysis of the use of social stories in teaching social skills to children with autism spectrum disorders.

Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice.

14(5),

Read Full

(New Window)

-

Bucholz J. L. (2012)

Social stories for children with autism: a review of the literature.

Journal of Special Education.

22(2),

Read Abstract

(New Window)

Read Full

(New Window)

-

Gray C. A., Garand J. D. (1993)

Social stories: Improving responses of students with autism with accurate social information.

Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities.

8

Read Abstract

(New Window)

-

Gray C. A. (2010)

Comparison of Social Stories 10.0 – 10.2 Criteria.

Read Full

(New Window)

-

Karkhaneh M.

et al.

(2010)

Social stories to improve social skills in children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review.

Autism.

14(6),

Read Abstract

(New Window)

-

Kokina A., Kern L. (2010)

Social story interventions for students with autism spectrum disorders: A meta-analysis.

Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders.

40(7),

Read Abstract

(New Window)

-

Mayton M. R.

et al.

(2013)

An analysis of social stories research using an evidence-based practice model.

Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs.

13(3),

Read Abstract

(New Window)

-

McGill R. J., Baker D., Busse R. T. (2015)

Social story interventions for decreasing challenging behaviours: A single-case meta-analysis 1995–2012.

Educational Psychology in Practice.

31(1),

Read Abstract

(New Window)

-

Nichols S. L.

et al.

(2005)

Review of social story interventions for children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders.

Journal of Evidence-Based Practices for Schools.

6(1),

-

Qi C. H.

et al.

A systematic review of effects of social stories interventions for individuals with autism spectrum disorder.

Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities.

Read Abstract

(New Window)

-

Reynhout G., Carter M. (2011)

Evaluation of the efficacy of social stories using three single subject metrics.

Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders.

5(2),

Read Abstract

(New Window)

-

Reynhout G., Carter M. (2006)

Social stories� for children with disabilities.

Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders.

36(4),

Read Abstract

(New Window)

-

Rhodes C. (2014)

Do social stories help to decrease disruptive behaviour in children with autistic spectrum disorders? A review of the published literature.

Journal of Intellectual Disabilities.

18(1),

Read Abstract

(New Window)

-

Rust J., Smith A. (2006)

How should the effectiveness of social stories to modify the behaviour of children on the autistic spectrum be tested?

Autism.

Read Abstract

(New Window)

-

Sansosti F. J. (2008)

Teaching social behavior to children with autism spectrum disorders using social stories: Implications for school-based practice.

Journal of Speech-Language Pathology and Applied Behavior Analysis.

4(1),

Read Full

(New Window)

-

Sansosti F. J., Powell-Smith K. A., Kincaid D. (2004)

A research synthesis of social story interventions for children with autism spectrum disorders.

Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities.

19(4),

Read Abstract

(New Window)

Read Full

(New Window)

-

Stary A. K.

et al.

(2012)

Social stories for children with autism spectrum disorders: Updated review of the literature from 2004 to 2010.

Journal of Evidence-Based Practices for Schools.

13(2),

-

Styles A. (2011)

Social stories: does the research evidence support the popularity?

Educational Psychology in Practice.

27(4),

Read Abstract

(New Window)

-

Test D. W.

et al.

(2011)

A comprehensive review and meta-analysis of the social stories literature.

Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities.

26

Read Abstract

(New Window)

Additional Information

Carol Gray has published various versions of the defining characteristics of social stories. The latest version, “Social Stories 10.2”, was published in 2014 and is reproduced below.

The Social Story Goal. Authors follow a defined process to share accurate information using a content, format, and voice that is descriptive, meaningful, and physically, socially, and emotionally safe for the Audience.

Two-Step Discovery. Authors gather information to 1) improve their understanding of the Audience in relation to a situation, skill, or concept and 2) identify the topic and focus of each Story/Article. At least 50% of all Social Stories applaud achievements.

Three Parts and a Title. A Social Story/Article has a title and introduction that clearly identifies the topic, a body that adds detail, and a conclusion that reinforces and summarizes the information.

FOURmat. The Social Story format is tailored to the individual abilities, attention span, learning style and - whenever possible – talents and/or interests of its Audience

Five Factors Define Voice and Vocabulary. A Social Story™/Article has a patient and supportive “voice” and vocabulary that is defined by five factors. These factors are: 1) First- or Third-Person Perspective; 2) Past, Present, and/or Future Tense; 3) Positive and Patient Tone; 4) Literal Accuracy; and 5) Accurate Meaning.

Six Questions Guide Story Development. A Social Story answers relevant ’wh‘ questions that describe context, including place (WHERE), time-related information (WHEN),relevant people (WHO), important cues (WHAT), basic activities, behaviors, or statements (HOW), and the reasons or rationale behind them (WHY).

Seven is About Sentences. A Social Story is comprised of Descriptive Sentences, as well as optional Coaching Sentences. Descriptive Sentences accurately describe relevant aspects of context, including external and internal factors, while adhering to all applicable Social Story Criteria.

A GR-EIGHT Formula. One Formula ensures that every Social Story describes more than directs.

Nine to Refine. A story draft is always reviewed and revised if necessary to ensure that it meets all defining Social Story criteria.

Ten Guides to Implementation. The Ten Guides to Implementation ensure that the Goal that guides Story/Article development is also evident in its use. They are: 1) Plan for Comprehension; 2) Plan Story Support; 3) Plan Story Review; 4) Plan a Positive Introduction; 5) Monitor; 6) Organize the Stories; 7) Mix & Match to Build Concepts; 8) Story Re-runs and Sequels to Tie Past, Present, and Future; 9) Recycle Instruction into Applause; 10) Stay Current on Social Story Research and Updates.

Related Additional Information

- Updated

- 17 Jun 2022

- Last Review

- 01 Jul 2017

- Next Review

- 01 Oct 2023